California Capital Gains Tax works just like income tax—the state treats profits from selling stocks, bonds, real estate, or other assets as ordinary income.

Unlike the federal government, which separates short-term and long-term capital gains, California makes no distinction.

Whether you held an asset for 10 days or 10 years, your profit is taxed using the state’s progressive income tax brackets, with rates reaching as high as 13.3%.

That means a big gain could easily bump you into a higher tax bracket and significantly increase the amount you owe.

In this guide, I’ll break down:

- California’s 2026 capital gains tax rates (with real-world examples)

- How federal capital gains tax works (and why timing matters)

- Real estate capital gains rules in California — including Prop 19 implications

- Smart strategies to legally reduce your tax bill

- Common mistakes California residents make with capital gains

By the end, you’ll know exactly how California Capital Gains Tax is calculated, what the combined federal and state tax rate looks like at your income level, and what you can do to keep more of your money.

Key Takeaways

-

California taxes capital gains as ordinary income, with no difference between short-term and long-term holdings.

-

Large gains can push you into higher state tax brackets, increasing how much you owe.

-

Strategies like tax-loss harvesting, installment sales, and charitable giving can help reduce your overall capital gains tax burden.

How Much Is Capital Gains Tax in California?

California taxes capital gains the same way it taxes wages—by treating them as regular income.

This means any profit from selling stocks, bonds, real estate, or other assets is taxed according to the state’s ordinary income tax rates.

There is no distinction between short-term and long-term capital gains tax rates for 2026 at the state level.

Whether you held the asset for one week or 15 years, your gain is taxed as part of your taxable income under the state’s progressive system.

If your capital gain is significant, it can move you into a higher tax bracket, which affects how much you’ll ultimately owe on your tax returns.

Here’s a simplified look at California’s 2026 personal income tax brackets for single filers, which also apply to capital gains (1):

- 1% rate – Taxable income up to $11,079

- 2% rate – $11,080 – $26,264

- 4% rate – $26,265 – $41,496

- 6% rate – $41,497 – $57,516

- 8% rate – $57,517 – $73,783

- 9.3% rate – $73,784 – $377,778

- 10.3% rate – $377,779 – $453,442

- 11.3% rate – $453,443 – $757,704

- 12.3% rate – $757,705 – $1,000,000

- 13.3% rate (includes 1% Mental Health Services Tax) – Over $1,000,000

Federal Capital Gains Tax Rates for 2026

Unlike California, the Federal government bases capital gains taxes on holding periods.

For 2026, there is a clear distinction between short-term and long-term capital gains tax rates, which can influence your timing strategy when selling investments.

2026 Short-Term Capital Gains

If you hold an asset for a year or shorter, your gain is taxed as regular income.

These profits are subject to the same income tax rates and can push you into a higher tax bracket, especially if the gain is significant.

Short-term capital gains can be taxed at rates ranging from 10% to 37%, depending on your total income (2).

2026 Long-Term Capital Gains

If you hold the asset for longer than a year, your gain is typically taxed at a reduced rate.

These federal capital gains tax rates for 2026 vary by income and filing status (3):

- 0% rate

- Single: $0 – $48,601

- Married filing jointly: $0 – $97,202

- Married filing separately: $0 – $48,601

- Head of household: $0 – $65,100

- 15% rate

- Single: $48,602 – $535,100

- Married filing jointly: $97,203 – $608,350

- Married filing separately: $48,602 – $304,175

- Head of household: $65,101 – $572,350

- 20% rate

- Single: $535,101 and above

- Married filing jointly: $608,351 and above

- Married filing separately: $304,176 and above

- Head of household: $572,351 and above

Please Note: In addition, higher earners may face the net investment income tax (NIIT)—an extra 3.8% federal surcharge that applies to capital gains and other passive income if your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds certain thresholds. Additionally, long-term gains on certain tangible assets like art, rare coins, or precious metals may face a higher maximum tax rate of 28% rather than the usual capital gains rates (3).

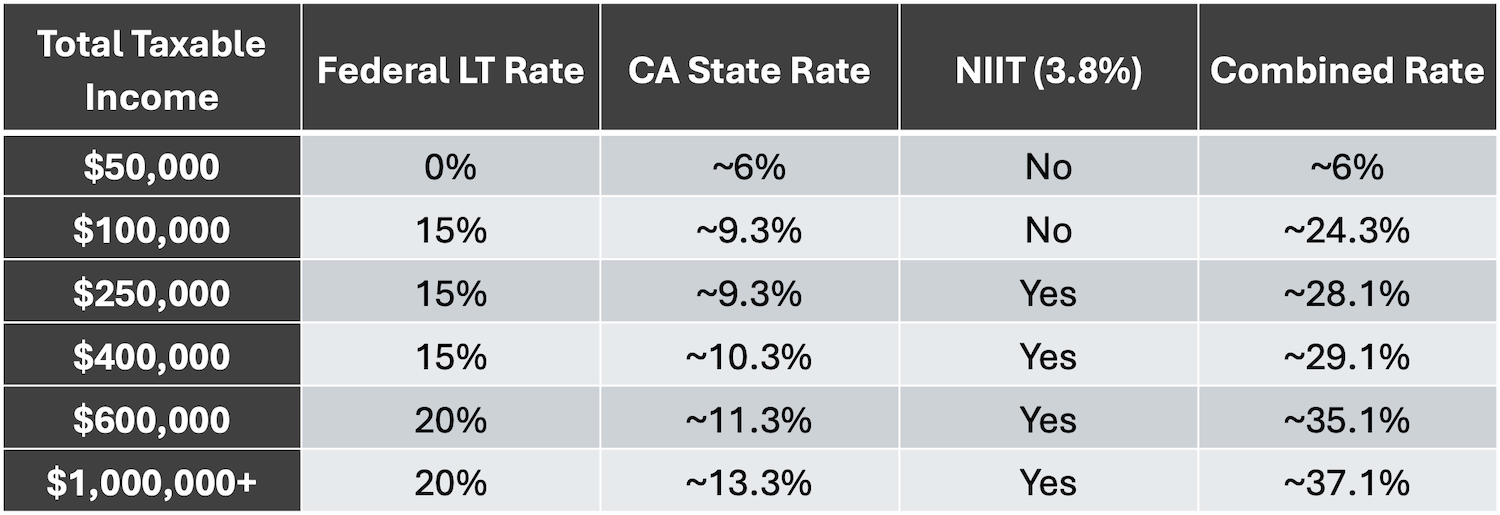

Combined Federal + California Capital Gains Tax Rates

Understanding your California rate or your federal rate in isolation doesn’t tell you what you’ll actually owe.

What matters is the combined effective rate—the total percentage of your capital gain that goes to taxes.

The table below shows estimated combined tax rates for a single filer selling a long-term capital asset in California at various income levels.

These figures include the federal long-term capital gains rate, the California state income tax rate, and the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), where applicable.

These are simplified estimates for illustration purposes. Your actual rate depends on your complete tax situation, filing status, deductions, and the interaction between your ordinary income and your capital gain.

The California rates shown reflect the marginal bracket your gain falls into, not your effective rate on all income.

As the table shows, a high-income California resident selling a long-term investment could lose more than a third of the gain to taxes.

For short-term gains (held one year or less), the combined rate can exceed 50% at the highest income levels, since both federal and state tax the gain as ordinary income.

This is why timing, tax-loss harvesting, and coordination with lower-income years are so critical for California investors, and why the strategies outlined later in this guide can save tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Capital Gains Tax on Real Estate in California

Selling real estate in California can lead to unique considerations regarding these gains.

The state’s treatment of home sales and investment properties plays a major role in how much tax you’ll owe.

Additionally, homeowners might wonder how federal rules, such as exclusions for a primary residence, apply at the state level.

This section will look at several areas that often spark questions regarding these topics:

Exclusions for primary residences: Federal guidelines allow you to exclude up to $250,000 of capital gains on the sale of a qualifying primary residence if you file singly, and up to $500,000 if married and filing jointly. California generally aligns with this approach. However, if your gain exceeds these amounts, the state taxes that extra portion as ordinary income.

Rental property sales and depreciation recapture: When you sell rental property, you’ll owe capital gains tax not only on the property’s appreciation but also on the depreciation you claimed during ownership. At the federal level, this “depreciation recapture” is taxed separately at your ordinary income tax rate, capped at a maximum of 25% (4). California, however, does not apply a distinct recapture rate. Instead, the entire gain—including the depreciation portion—is added to your ordinary income and taxed according to your state income bracket.

Inherited real estate and step-up in basis: If you inherit property, the basis is “stepped up” to fair market value at the time of inheritance. California follows federal guidelines in this regard, which can reduce or eliminate the gains if you decide to sell soon afterward. Still, if the property appreciates further after the date of inheritance, you’ll owe tax on that portion of the profit.

1031 exchanges: You can defer the gain from selling a property if you purchase a “like-kind” property under Section 1031. This approach allows you to delay paying taxes to both the federal government and the state, although California will require tracking of the deferred gain. If the replacement property is located out of state and subsequently sold in a taxable transaction, California will require taxes on the originally deferred gain through its clawback provision..

How to Calculate Capital Gains in California

Determining your gains involves examining costs, improvements, and various adjustments that can increase or decrease your final profit.

The process typically starts with federal calculations and flows through to California’s tax return.

It helps to have solid documentation—especially when assets have been held for an extended time or in cases where improvements have increased their value:

Cost basis and recordkeeping

Your cost basis typically starts with the purchase price. If you bought a property or set of shares, that initial figure is your baseline. For property, any improvements that add to the property’s value (such as a home remodel) increase your basis. If you have sold or upgraded part of an asset, thorough records will help confirm the correct amount.

Adjustments to basis

Various expenses, including realtor commissions, closing fees, or renovation costs, can boost your basis, which reduces the ultimate gain. It’s wise to keep receipts and documentation for these transactions because forgetting them can lead to paying tax on more profit than you truly earned.

Depreciation recapture implications

For rental or business property, you might have taken depreciation deductions over time. That amount comes back into play at the point of sale, increasing the reported gain. At the federal level, recaptured depreciation may be taxed at an increased rate, capped at 25%. The amount is also included in your California return, where it is taxed as ordinary income.

Federal calculation followed by state taxation

Once the total gain is determined under federal rules, California treats the profit differently. While federal tax rules give preferential treatment to long-term investments, California does not distinguish between holding periods. Instead, the entire amount is taxed as ordinary income under the state’s progressive tax rates for long and short holdings alike.

Strategies to Reduce Capital Gains Tax in California

Selling a property or investment and then handing over a significant portion of your profit is never ideal.

Fortunately, there are tactics that could lessen how much you owe.

Some of these options apply primarily at the federal level but can still influence your financial decisions—especially since California taxes capital gains as ordinary income.

While the state won’t cut you a break on the rate, reducing your taxable gains can still lower what you owe overall.

Here are some strategies you have at your disposal:

Tax-loss harvesting

If you have positions in your portfolio that are underwater, selling those losing investments may offset some of your gains for the year. You cannot buy the same or very similar security shortly before or after this sale; however, you may choose to reinvest in something different. Using this method, you can soften the blow of your overall gain, reducing the amount the state will see as income.

Holding period

Many investors attempt to hold assets for over one year so that the gains qualify for the lower federal rate. While California does not differentiate between shorter or longer terms, your federal liability could still shrink by waiting. Delaying a sale may also be beneficial if you anticipate a lower income in a future year, making the overall tax impact more manageable.

Installment sales strategy

Sometimes, sellers choose to spread the proceeds of a sale over multiple years, so the total profit doesn’t land in a single return. If you have a buyer willing to pay in installments, you can tackle your obligations more gradually. This method prevents you from receiving a lump sum that might otherwise push you into a higher tax bracket immediately.

Charitable giving of appreciated assets

Donating appreciated assets—like shares of stock—to a qualified organization may help you sidestep a tax hit on the built-in gain. You typically receive a deduction for the full market value, thereby avoiding the recognition of gain that would occur if you sold first. While this is a federal concept, it indirectly affects what appears on your California forms, as the gain is never reported.

Gifting to lower-income family members

In certain instances, families may gift assets to relatives in lower brackets to reduce the total amount owed across the family as a whole. If the recipient sells later, their rate could be lower. This practice must be approached carefully because transferring valuable property does have potential impacts—particularly if the family member also resides in California.

Using donor-advised funds or charitable trusts

High-net-worth individuals sometimes consider donor-advised funds or charitable trusts as a means to donate assets without triggering immediate capital gains. Donor-advised funds allow you to contribute stock or other property and then distribute the funds to charities over time. These paths can result in a smaller overall tax bill, especially when combined with proper planning at the federal level.

Coordinating with retirement timelines

Your overall earnings may drop once you scale back on work. If you wait until a year when you expect less income, your sale could come with fewer overall taxes. This is especially relevant if you plan to take bigger withdrawals from retirement accounts in the future. Timing large transactions during low-income years may help limit the portion of your gain taxed at higher rates.

Additional Exemptions and Special Situations

Certain rules can affect how California taxes your investment gains.

For example, while federal law under Section 1202 may allow you to exclude some or all of the gain from selling Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS), California does not conform to this rule (5).

So, even if you’re exempt at the federal level, the gain may still be taxable by the state.

Additionally, retirement accounts like IRAs and 401(k)s allow you to defer taxes on investment gains until withdrawal.

When you begin withdrawing funds, the entire distribution is treated as regular income for tax purposes—not as capital gains.

Taking out a significant amount in a single year can bump your income into a higher bracket, leading to a larger overall tax bill.

Capital Gains Tax in California FAQs

Many people have common follow-up questions once they realize how California treats profits on the sale of property or investments. Below are a few that frequently arise.

1. Do I owe capital gains tax if I sell my California home?

It depends on the size of your gain. If the home qualifies as your primary residence and you’ve lived there for at least two of the last five years, you can exclude up to $250,000 (single) or $500,000 (married filing jointly) from taxes. Any gain above those thresholds is taxed as ordinary income by California.

2. Does California tax out-of-state capital gains?

Yes. California taxes its residents on all income, regardless of where it was earned, including gains from out-of-state investments and property. If you are a California resident, when you sell an appreciated asset — even one located in another state — the gain is taxable by California

3. What happens if I move out of California before selling an appreciated asset?

For real property located in California, you’ll still owe California tax on the gain regardless of where you live when you sell. For intangible assets like stocks, bonds, and cryptocurrency, establishing genuine residency in another state before the sale generally means California cannot tax the gain, but the Franchise Tax Board may audit your residency change if a large gain is involved

4. How are capital gains treated for inherited property in California?

Inherited property receives a stepped-up basis to its fair market value at the date of the previous owner’s death, following federal rules. This means if you sell shortly after inheriting, the taxable gain may be small or zero. Only appreciation that occurs after the inheritance date is subject to California capital gains tax.”

5. Can capital gains push me into a higher California tax bracket?

Yes — this is one of the most common surprises for California taxpayers. Because the state taxes capital gains as ordinary income, a large gain is added on top of your salary, retirement income, and other earnings. This combined total determines your marginal tax bracket, which means a single large sale could push you from a 9.3% bracket into the 11.3% or even 13.3% bracket.”

Let us Help You With Capital Gains Tax Planning in California

California’s tax treatment of capital gains catches many investors off guard—particularly because the state makes no distinction between short-term and long-term holdings, and rates can reach as high as 13.3%.

Whether you’re preparing to sell a rental property, cash out a concentrated stock position, or manage the tax impact of business interests, understanding how timing, income, and asset type interact with your tax bill is critical to protecting your wealth.

From the 3.8% federal NIIT surcharge to depreciation recapture, bracket stacking, and California’s 1031 exchange clawback rules, the details add up quickly.

A proactive plan—whether through tax-loss harvesting, installment sales, charitable giving, or coordinating with lower-income retirement years—can reduce the impact of these taxes and keep more of your gains working for you.

Our financial advisory team specializes in tax-smart retirement planning for California residents aged 50 and older.

We can work with you to evaluate your full tax picture, model different sale timing scenarios, and coordinate with your CPA or estate planning attorney as needed.

Schedule a complimentary Retirement Strategy Session with our team today to get personalized guidance on your capital gains tax situation.

Taylor Schulte, CFP® is the founder & CEO of Define Financial, a fee-only wealth management firm in San Diego, CA specializing in retirement planning for people over age 50. Schulte is a regular contributor to Kiplinger and his commentary is regularly featured in publications such as The Wall Street Journal, CNBC, Forbes, Bloomberg, and the San Diego Business Journal.