Some people argue that exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are always better than mutual funds.

But is this true?

It’s time to set the record straight.

Let’s clear the air surrounding this wonderful investment vehicle: the good ol’ mutual fund.

If you have always wanted to know the difference between mutual funds and ETFs, you will enjoy today’s post.

The Basics of Investing

One of the biggest problems in the mutual fund vs. ETF debate stems from a misunderstanding of how investing works. To best explain this, we’ll cover some investing basics first. To keep things simple, we’re going to start our discussion on regular (meaning taxable) investment accounts.

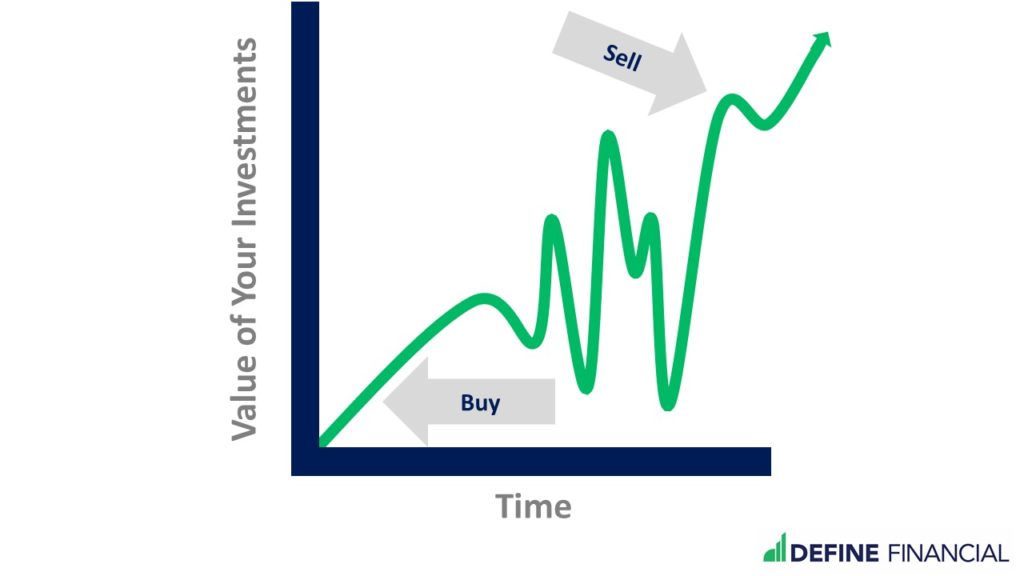

How to Invest: Buy. Sell.

When you get down to it, investing is pretty simple:

Buy low. Sell high.

But this overlooks a crucial step in the middle: waiting.

Buy low. Wait. Sell high.

In investing, waiting is key. That’s because holding your investments long enough means:

- You increase your chances of selling your investment for more than you bought it. (Investments can be stocks, bonds, funds, or something else.)

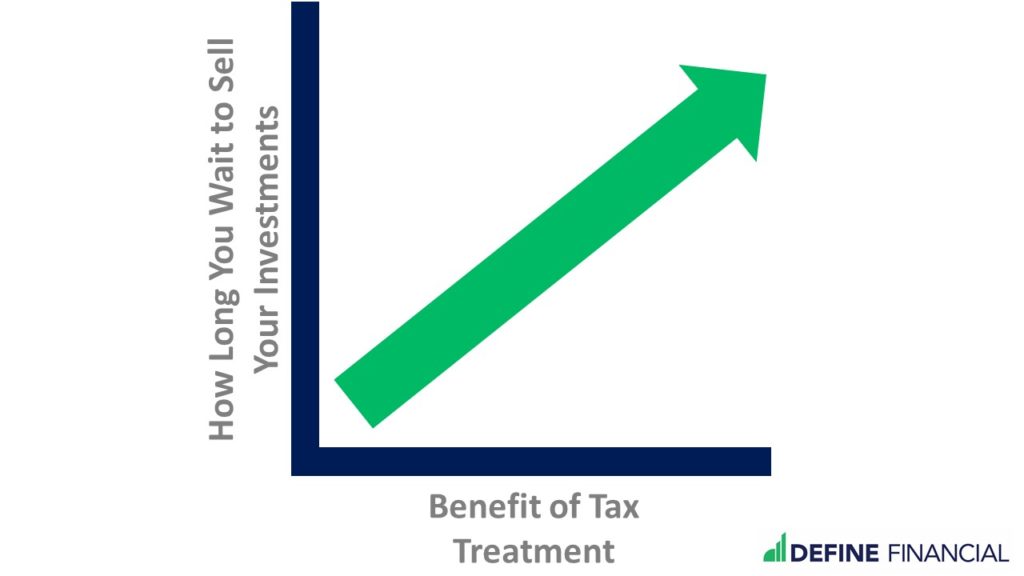

- The U.S. government will reward you with better tax treatment if you hold your investment for at least a year.

The longer you wait to sell your investments, the greater the tax benefit.

How often you buy and sell your investments is referred to as “turnover.” We won’t get into the calculations of turnover in this post. Just know limiting turnover can help you keep your investment expenses low and take advantage of beneficial tax treatment.

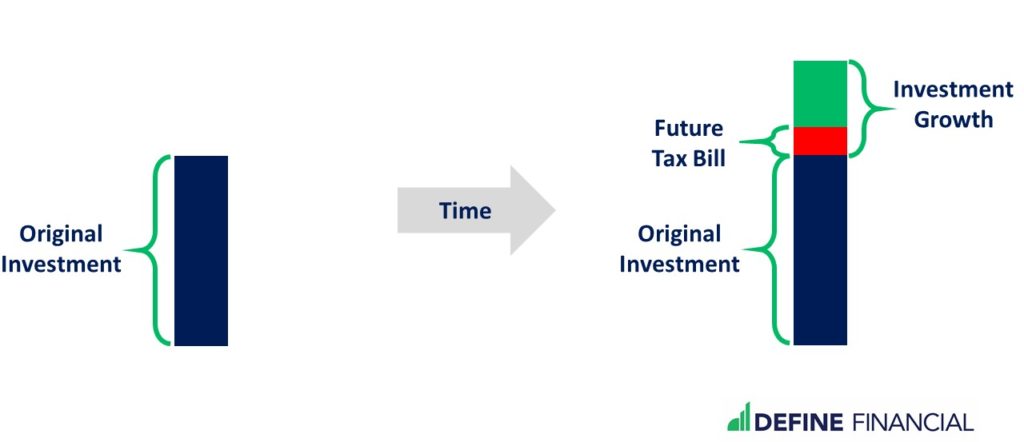

Deferred Taxes on Growth in Taxable Investment Accounts

In a regular (taxable) investment account, you don’t pay taxes on the increase in the value of your investment until you sell it. The longer you put off selling (or the lower your turnover), the longer you can delay paying taxes.

Minimizing investment turnover helps you take advantage of beneficial tax treatment.

This is an important point worth repeating: In a regular taxable account, the longer you wait to sell an investment, the longer you delay paying taxes on that sale. But why does this matter? If you have to pay the tax anyway, does it really matter when?

The answer: the longer you postpone giving your money to Uncle Sam, the longer you can make the money work for you.

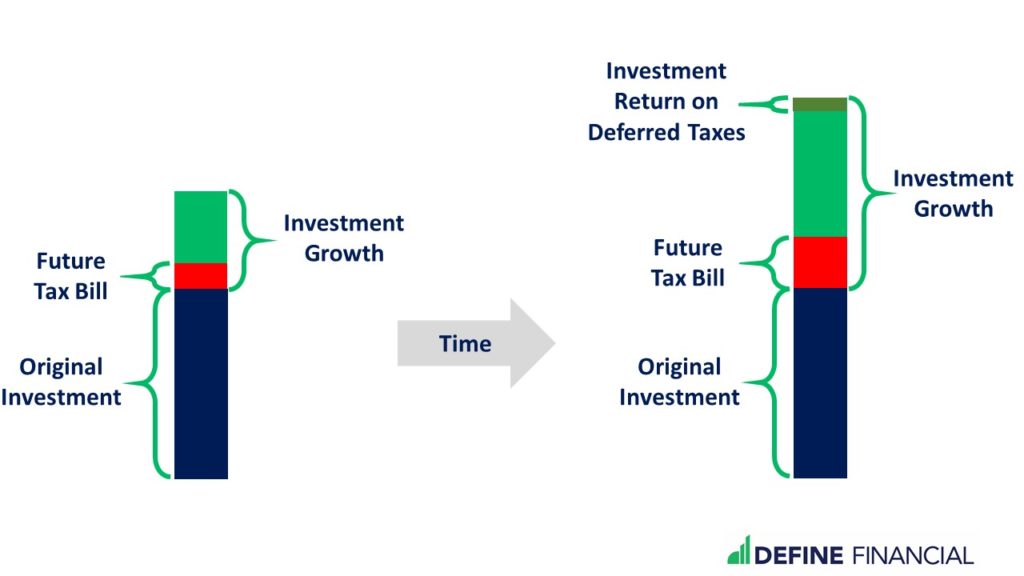

Re-Investing Your Deferred Tax Bill

By holding onto your investment, you’ve legally delayed your tax bill; your money is yours for longer and you can put it to work.

How can you make your delayed tax bill work for you? Re-invest it. Put the amount that you would have paid in taxes back into the market for further growth.

Here’s an example:

You invested $100,000 in a low-cost index fund. One year later, that $100,000 has grown to $110,000. Congratulations: You just made $10,000!

Imagine you are in the 20% long-term tax bracket. If you sell your investment (assuming you’ve held the investment for at least one year), you would owe that tax rate of 20% on that $10,000 growth. That comes to a tax bill of $2,000.

But you’re not going to sell. You decide to hold on to your investment for one more year. By doing this, you defer the tax expense. That means that this year, Uncle Sam has effectively loaned you $2,000.

What should you do with that $2,000? Re-invest it!

Re-investing your future $2,000 tax bill means, assuming a 10% annual rate of return, you’ll have $2,200 by the end of the year. That’s an extra $200 of investment growth, all because you reinvested the $2,000 that Uncle Sam lent you.

That is the power of reinvesting your deferred taxes. The more you have to invest (and re-invest), the higher your earning potential.

Investing Taxes: Appreciation vs. Distributions

We’ve just covered the tax consequences when your investments increase in value. You likely don’t need me to tell you that when your investment “appreciates”, you make money. But your investment can also make you money in another way, via a distribution.

Next, we’ll cover the difference between appreciation and distributions and what that means for your taxes.

Investing Appreciation

If something appreciates in value, it is worth more.

Consider a home: Let’s say you’ve owned a home for many years. Even though the value of your home has steadily increased over the years, you’re not paying taxes every year on that growth in value, right?

Of course not! That’s because you don’t have to pay taxes on appreciation in value until you sell your home. Taxes are deferred – or delayed – on the appreciation.

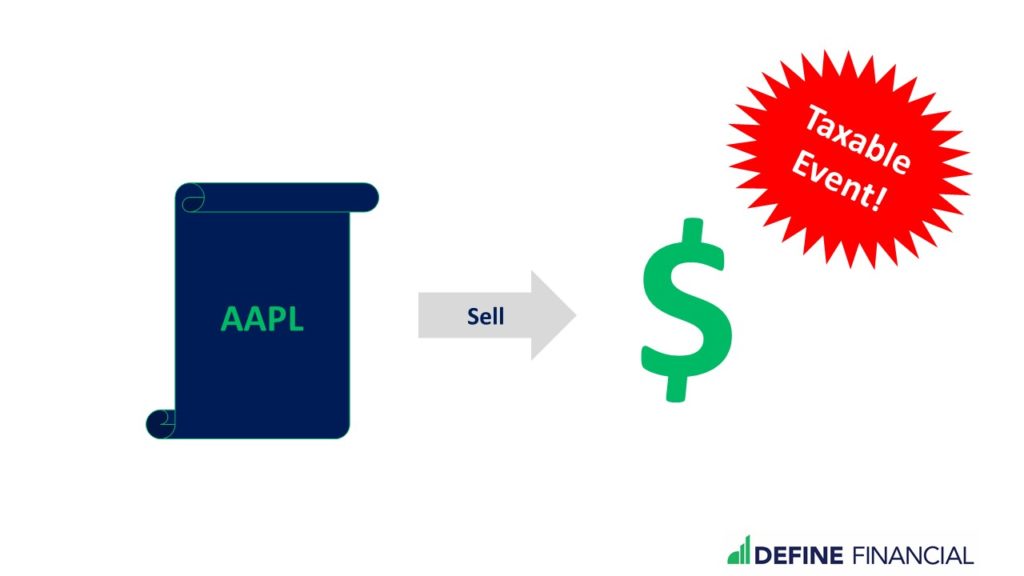

The same goes for your investments. Your investments can increase in value, but that appreciation is not taxed until you sell the investment. (The sale is what’s known as a taxable event).

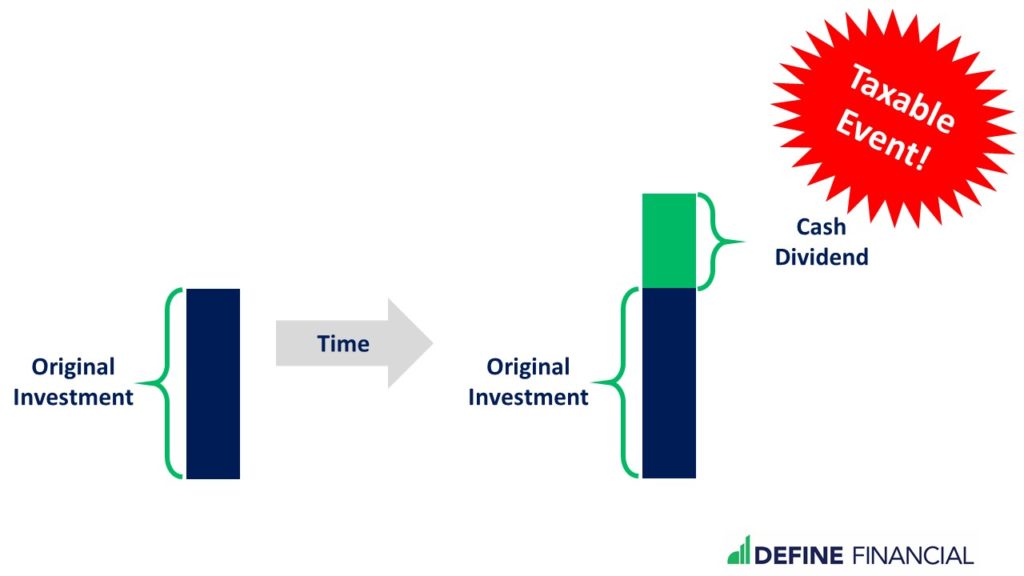

Distributions

Distributions are disbursements to the owners of an investment. Sometimes, this means a stock issuing a cash dividend. Other times, it’s a bond making a coupon payment. These distributions are considered “income.” (The distribution is the taxable event).

Distributions get taxed in the year they are received.

Dividends and coupons are distributions. Distributions are a taxable event. You must pay taxes each year you receive a cash dividend from a stock or a bond’s coupon payment.

Investment example:

You bought several shares of Apple stock in 2019. It’s now 2020, and Apple’s share price has increased. You don’t sell the shares.

Because you’re not selling your Apple shares this year, you don’t owe taxes on the appreciation. Without a sale, there is no taxable event. Even though your shares of Apple stock are worth more, your taxes are deferred.

However, you do receive a check from Apple as a dividend (a distribution of money to the shareholders).

The check you receive from Apple is dividend income; it is subject to income taxes that very year.

Tax Side Bar: Tax-Advantaged Retirement Plans

So far, we’ve discussed regular taxable accounts. In retirement plans likes IRAs and 401(k)s, the tax treatment is somewhat similar: you defer the tax bill until you withdraw your money (the taxable event). The longer you let the money stay inside the account (be it a 401(k) IRA, or similar), the longer you put off paying taxes.

Once again, Uncle Sam is loaning you your tax bill – which you can then reinvest and make more money.

Now that we’ve covered some tax basics, let’s continue with a few other Investing 101’s.

Mutual Funds & Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) Provide Diversification

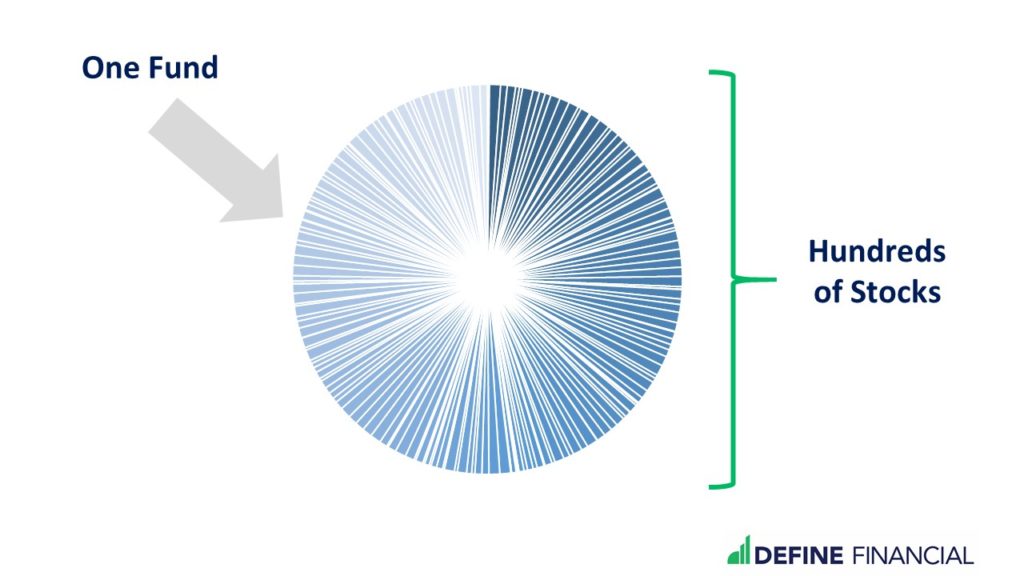

Before the invention of funds, an investor had to buy individual stocks to achieve a diversified portfolio. Nowadays, an investor can pick a single fund to achieve the same diversification. One fund has the ability to invest in thousands of stocks.

A single mutual fund or exchange traded-fund can invest in literally thousands of stocks.

Both mutual funds and exchange-traded funds are equally capable of providing portfolio diversification.

Pay Attention to Investment Fees

Here’s one more important investing concept: managing costs is critical to investment success.

All else being equal, the more you spend on investment expenses, the less you will have leftover to invest. For this reason, it is essential to keep investing expenses low. And keeping turnover low is one way to help lower investment expenses.

The Basics of Investing: A Recap

Before moving on, let’s recap the important investing basics we’ve covered so far:

- Investing is buying, waiting, and then selling.

- The longer you wait to sell (or the lower your turnover), the greater the tax advantage.

- Both mutual funds and ETFs provide portfolio diversification.

- Keeping investment expenses low is critical to investing success.

Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) vs. Mutual Funds

Next, let’s talk about how ETFs can offer a tax advantage over mutual funds.

Selling appreciated stock can be a taxable event. You’ll owe taxes for that tax year.

If you own a share of appreciated Apple stock – and then sell it – you get a tax bill. It’s a tax bill that you’ll have to pay that tax year.

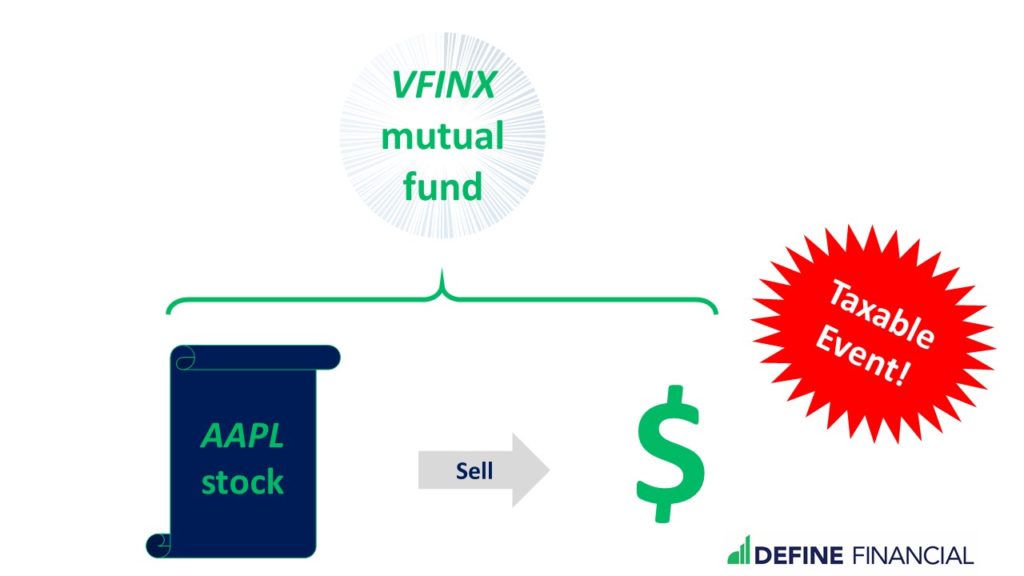

The same goes if you own a mutual fund that sells some Apple stock. If the mutual fund you own sells appreciated Apple stock, you get a tax bill.

If a mutual fund you own sells appreciated stock, you may owe taxes for that tax year.

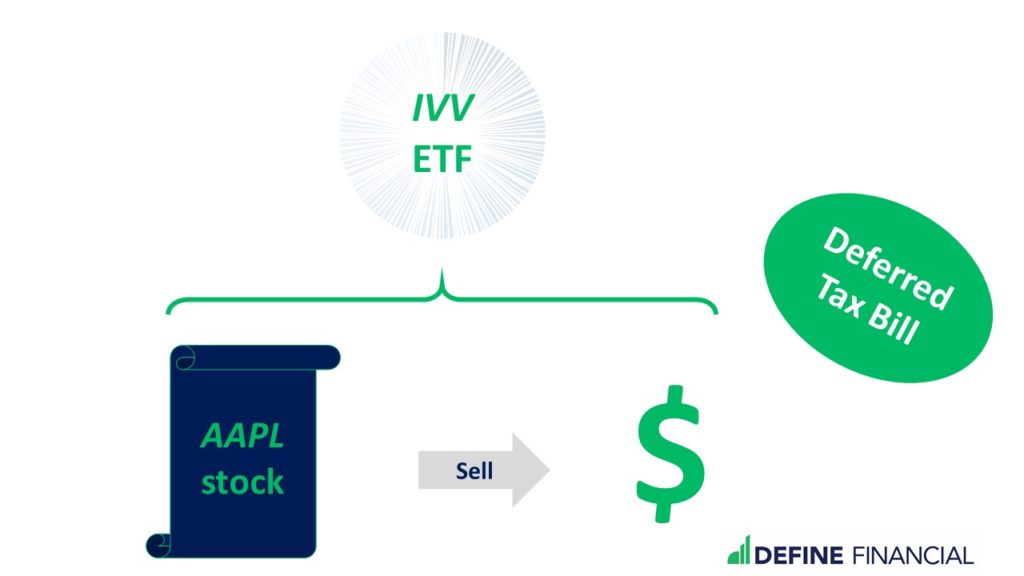

But, that isn’t always the case for ETFs. If an ETF sells appreciated Apple stock, there is a good chance that the ETF can defer that tax bill. That means even though the ETF sold Apple stock for a profit, you won’t have to pay taxes until you sell the ETF.

ETFs may be able to defer capital gains. That means you may not have to pay any taxes with an ETF until you sell that ETF.

Tax Efficiency Doesn’t Mean Not Paying Taxes

If you make money, you’re going to have to pay taxes. (But hey, the good news is you made money, right?)

While ETFs can sometimes defer taxes better than mutual funds, you will eventually have to pay taxes on your gains. Investing with an ETF over a mutual may help you postpone paying your tax bill – but not avoid it entirely.

How Much Better are ETFs at Managing Taxes than Mutual Funds?

That’s a great question. It depends on who you ask – and your investment strategy. Studies exploring the subject are few – and the results arguable. Whatsmore, the answers have varied wildly: from a low of 0.12% to a high of 1.19%.

Now that we’ve covered the basics of investing and how ETFs and mutual funds are different, we can move onto the real purpose of this discussion: what is the confusion between mutual funds and ETFs, and why is it a mistake to think that ETFs are wholly better than mutual funds?

Misunderstanding #1: Mutual Funds are More Expensive than ETFs

Before investors learned to pay attention to investment expenses, high fees were the industry norm. Since mutual funds have been around longer than ETFs, they became associated with high expenses. But that’s not always the case; it’s just the environment they were born into.

Once the younger, newer Exchange-Traded Funds entered the investment scene, they became associated with low-cost investing. In contrast to the seemingly outdated mutual fund, ETFs were assumed to be inherently better because they were less expensive.

Mutual funds can be low- or high-cost. You need to shop around to find a low-cost mutual fund.

In reality, mutual funds have caught up with the times. Generally speaking, newer mutual funds are now as low-cost as ETFs, though they struggle to shed their old image. Some older, more expensive mutual funds remain – but that doesn’t mean you need to invest in them.

Throwing Out the Baby with the Bath Water: Expensive Funds are the Problem

In the attempt to simplify investing, many folks throw the baby out with the bathwater!

High fees are the problem – not the mutual funds themselves. As a smart investor, choose your funds with an eye on the real problem: high investment expenses.

Consider an example:

General Motors manufactures a variety of cars. Some of their SUVs get hilariously bad gas mileage, but they also make fully electric cars that use no gas at all. If your goal is to use less gas, do you rule out all of GM’s vehicles?

Of course not! You only exclude the cars that don’t meet your goal of getting better gas mileage.

Selecting an ETF doesn’t guarantee you low expenses. Not all ETFs are low-cost.

It’s the same thing for mutual funds. Given our goal of keeping expenses low, we don’t want to rule out all mutual funds. We only rule out those expensive mutual funds that don’t meet our goal of keeping investment expenses low.

There are fantastic ultra-low-cost mutual funds out there, and some are even free!

Not All ETFs are Low-Cost

On the flip side, just as there is an assumption that all mutual funds have high expense ratios, it is equally erroneous to think that all ETFs are low cost. Very expensive ETFs do exist. Roughly 16% of ETFs are not low-cost funds.

Misunderstanding #2: You Need an ETF to Shield You from Taxes

The second common misunderstanding is that you need ETFs to shield you from a big tax bill.

As explained above, ETFs can shield you from some taxes that mutual funds can’t. However, this logic conveniently ignores a few things.

A Solution for a Problem that You Probably Shouldn’t Have: Don’t Create a Huge Tax Bill

When I was in high school, I was really into cars. Like any teenage boy, I tended to drive over the speed limit. As a solution to my deviance, I bought a radar detector. The radar detector would let me know if any area law enforcement was measuring the speed of vehicles passing by.

For perspective, consider my misguided “solution” to breaking the law (i.e. speeding): I purchased a radar detector. However, the real solution would have been not to drive over the speed limit.

It’s the same for investing. Don’t forget one of our investing basics: the longer you wait to sell, the greater the tax advantage. That’s because selling your investment creates a taxable event.

When you sell your investments, not only do you owe taxes, but you also incur transaction fees. (And remember, we want to keep our investment expenses low!) In short, when we invest, we want to limit our turnover.

As investors, we want the funds that we invest in to behave the same way – limiting turnover to keep investment expenses low. This should be the case whether those funds are mutual funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Frequent trading (or high turnover) not only generates taxes, but also creates other investing expenses. If those taxes don’t eat away at your investment return, the cost of frequent trading certainly can.

We’ve covered a lot of content in this section, let’s do a quick summary.

- ETFs can be better at deferring (not avoiding) taxes than mutual funds.

- There are both high- and low-cost mutual funds and high- and low-cost ETFs.

- We don’t want to invest in a fund (mutual fund or ETF) that trades too frequently – one that has high turnover. Even though we may be able to defer taxes from frequent sales with an ETF, we may not come out ahead after the expenses from frequent buying and selling. That’s because – taxes aside – trading costs money.

Skip Bond Exchange-Traded Funds

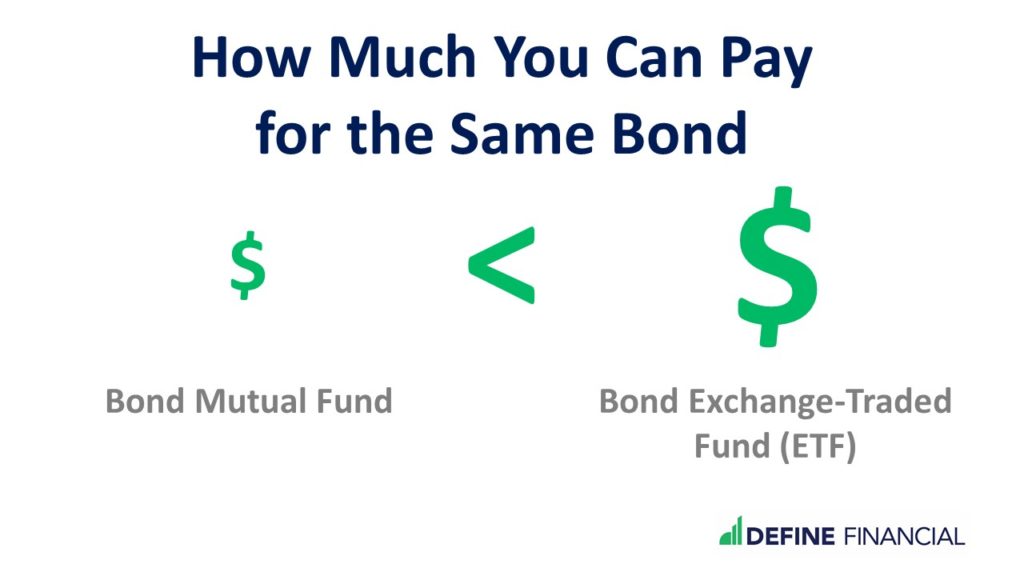

The above discussion was focused on mutual funds and ETFs that hold stocks. Of course, since both ETFs and mutual funds can (and do) hold bonds, there’s another point worth mentioning: don’t use bond ETFs.

During a liquidity squeeze, those bonds with low volume can demand a premium or discount that a bond ETF will have to pay.

William Berstein argues that bond ETFs should be skipped entirely. (Bernstein’s argument relates only to those ETFs that hold bonds other than U.S. Treasury bonds.) That’s because there can be problems trading corporate and municipal bonds when using ETFs. I’ll spare the details about trading liquidity. Here are the cliff notes: investors in a corporate bond ETF could end up paying more for the same bonds than investors in a corporate bond mutual fund.

Should I Switch to ETFs for the Tax Benefit?

Like all good questions, the answer to this question is: “It depends.”

A switch from mutual fund to exchange-traded fund is a taxable event. You’d be selling your mutual fund and buying ETFs. If switching, an important consideration is how much appreciation you have in your current mutual fund holdings: if you sell your mutual funds, will you be realizing significant taxable gains?

Hint: If you’ve held these mutual funds for a while, the answer should be “yes.” If the answer isn’t “yes”, you should strongly reconsider your current investment holdings.

If considering switching from mutual funds to ETFs, also remember to examine the expenses and turnover of each fund.

If you’re currently holding mutual funds with little appreciation, high expenses, and high turnover, then the decision to switch to low-cost, low-turnover ETFs may be an easy one.